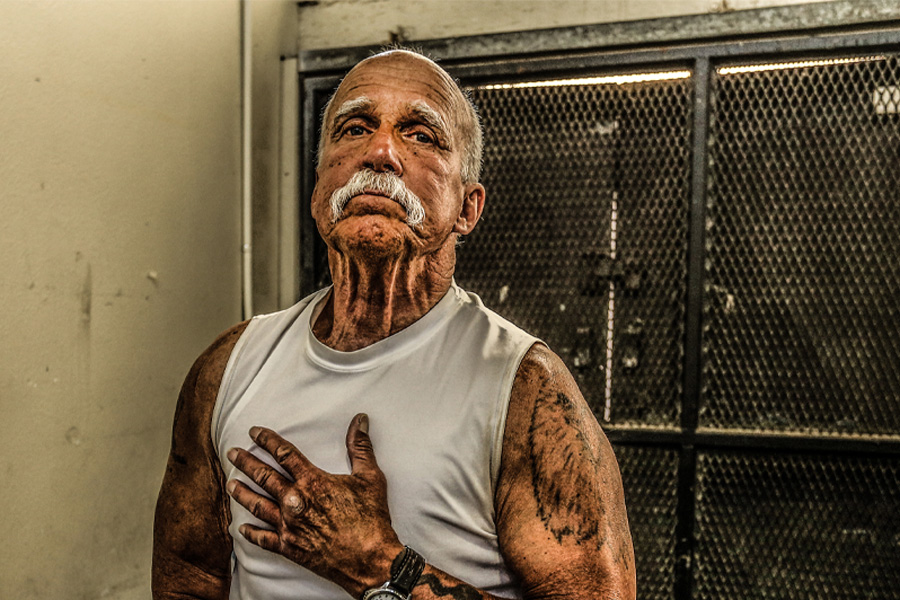

By Victor Reyes, Board Member & Facilitator, Prison Yoga Project; Colorado District Judge – Retired

Life-shifting epiphanies in the chaos of a maximum-security facility seem unfathomable. An environment where every human being, employees and incarcerated individuals alike, exists largely in fight, flight, or freeze is not the most fertile ground for deep reflection.

Having facilitated discussions for the past eight years in challenging environments, I have been privileged to witness an incredible amount of wisdom, born from lives shaped by adversity, trauma, and at times, tragedy.

Recently, however, I bore witness to something that stopped me in my tracks. I saw how a single comment could ignite the heart and open space for a conversation about mortality, meaning, and how we choose to live the time we have.

For the past seven weeks, a group of incarcerated men housed in the STAGES unit at USP Florence have been diving deeper into the impact of yoga on their lives using the Yoga and Mindfulness Immersion Workbook developed by Prison Yoga Project.

We began one session by sharing acts of self-compassion and compassion practiced during the previous week. Even within the confines of this environment, opportunities arose. Participants shared not only what they did, but how it felt in their bodies to engage in compassion. One man spoke about how much happier and lighter he felt on a daily basis after taking these teachings to heart, alongside other psychological tools he had been introduced to previously.

We then moved into Chapter 7, which focuses on resilience and rehabilitation, and discussed embodied awareness. I shared a personal exercise I had done prior to leading a traditional nine-point death meditation. I lived as if I were going to die at 6:00 p.m. that evening.

I described how that awareness sharpened my mental and physical presence throughout the day. I noticed how I interacted more deliberately, differentiated more clearly between what truly mattered and what did not, and found myself being kinder, gentler, and quicker to smile.

At that point, one participant, someone who rarely speaks, stopped me. He wanted to explore this idea further. How would we act if we truly knew death was imminent? He shared that this was a lens through which he had never viewed his relationship with the world.

He spoke about wanting to spend his final hours surrounded by family and loved ones. He yearned for love and connection. As he spoke, a sadness settled in the room. I wondered how many there knew that such a wish might not be possible for them.

He went on to say that if death were imminent, he would let go of the mask he has worn since growing up on the streets and living within institutions. Living in prison, he explained, you must portray yourself a certain way for respect and personal safety. He spoke of letting go of pride, of being able to tell the people he lives with how he truly feels about them.

He shared that he never really got to be a teenager. His father was imprisoned when he was fourteen or fifteen, and he adopted a gangster lifestyle, selling drugs to help provide for his family.

I asked him what it would feel like to let go of the mask.

“Relief,” he said. “Like a burden being lifted.”

The room fell silent. From the expressions and body language around him, it was clear his words had landed deeply. There were nods, small smiles, and a shared recognition. We talked then about the reality of living in a facility I cannot pretend to fully understand, and about how culture and community might shift toward balance and healing if a reasonable level of trust were possible. This consideration extends not only to the people in the unit, but also to the psychologists and correctional officers who spend their days there.

Even in that moment of safety, he noted that he had not yet expressed these feelings directly to anyone. He had only contemplated them through the lens of mortality.

To close, I shared Tom Petty’s song Walls. The lyric about building barricades around our island, the heart, “to keep out the danger and hold in the pain,” resonated deeply. Several men reflected on how much of their lives had been spent constructing walls, and how frightening the idea of dismantling them felt.

I shared a brief reflection about my own father, who grew up in a home with a violent alcoholic parent, and how that upbringing shaped his belief system around emotional suppression and a kind of faux machismo he tried to pass down.

We ended by reflecting on the reality that death is always just a breath away. Buddhist texts remind us that while the time of death is uncertain, we do have agency over how we act right now. I remember thinking about the courage it took for that man to speak so openly, a strength that should inspire us all. I did not tell him that day, but I intend to do so privately and appropriately when the moment comes.

While conversations about death and how to live meaningfully have existed for thousands of years across cultures, witnessing one unfold in a correctional setting felt profoundly unique. I have previously led the nine-point death meditation with younger incarcerated groups, where conversations ranged from fear to acceptance and toward living with intention.

We must always navigate the delicate balance between vulnerability and safety. As a volunteer, I find it essential to speak openly about this tension.

As Dr. Sigifredo Castell Britton wrote to me recently, following his Psychology Today article “Why Prison Often Fails to Change Behavior”:

“Meaningful change emerges when individuals feel seen, heard, and embodied again, even when trauma remains unnamed or unresolved. Conversations, breath, and movement often reopen pathways to self-recognition that institutional language alone cannot reach, especially for those who have long survived through disconnection.”

The reflections shared afterward by participants affirmed this truth:

“It opened my eyes and mind to a new way to not only relax, but also to deal with the stress that being in prison brings on a daily basis.”

“Being present and seeing clearly helps me notice my thoughts and emotions before reacting off negative impulse.”

“You taught me a new way to look at myself through breathing.”

Creating connection through meaningful conversation is especially vital in environments saturated with stress and fear. Not everyone is ready or able to engage fully in this kind of inner work. Mental health challenges, deep trauma, limited awareness of healing modalities, and a pervasive sense of unworthiness often stand in the way.

From more than forty years of experience across many facets of the justice system, I believe this deeply. If we genuinely want to address recidivism, whether in prisons, halfway houses, or probation, we must integrate systems designed for containment with ones that nurture heartfelt, substantive change.

Containment to compassion should be our aspiration, systemically and within our own lives.