By Jacque Crockford, PYP Facilitator

Where Do You Find Hope?

I have been teaching trauma-informed yoga with Prison Yoga Project (PYP) at Richard J. Donovan (RJD) Correctional Facility for the past eight years. Week after week, since 2017, I’ve sat in circles, stood in yards, moved through breath, and shared stillness alongside men who are largely forgotten by society. And every time—every single time—I find hope. But on this day, that hope felt especially loud.

Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility is a sprawling state prison south of San Diego, a few miles from the Mexico border. It houses nearly 4,000 incarcerated individuals, from maximum to minimum security.

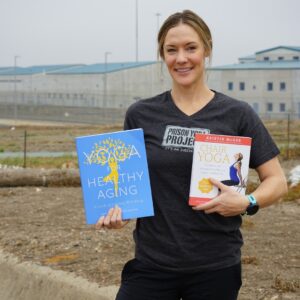

Back in April, I was there to represent Prison Yoga Project at an outreach table during Second Chance Day—part of Second Chance Month, an annual event recognized by the U.S. Senate to raise awareness about the barriers faced by people with criminal records and to promote opportunities for rehabilitation.

My role was to share information about our trauma-informed yoga program, which has taken place at RJD every Saturday since 2014. I met and chatted with residents, listened to their stories, and answered questions about yoga and our program.

Hope is getting a sunburn on a prison yard.

It was a beautiful SoCal day—blue skies, radiant desert sunshine, and a slight breeze weaving through fences, gates, razor wire, and concrete.

I visited with a man who has been incarcerated since he was 16 and is now nervous about an upcoming parole board hearing. We’re the same age. Another man, also about my age, talked about his dreams of becoming a chef and firefighter when he’s released—just two weeks away. Maybe it was the sun in our eyes, but I swear his eyes twinkled when he spoke about his future.

I met a trans woman—a veteran—who is eager to join our Saturday yoga class to support her healing.

The conversations were brief but deep.

Hope is watching grown men play like children.

For a few hours, the yard transformed into something like a small county fair—minus the livestock, though several therapy dogs were in attendance as usual.

Grown men, many who’ve spent decades behind bars, played ring toss, pseudo beer pong, Plinko, and lined up for a dunk tank. One man said how refreshing it was to be dunked—the full submersion brought him back to his days swimming and surfing.

There was music, candy, and joy. The therapy dogs looked up at their incarcerated handlers with the same excitement and love our pets give us on the outside.

It felt like a slow-motion montage of laughter, high fives, and humans—of all races, abilities, and ages—who forgot, for a moment, they were in prison.

Hope is knowing that rehabilitation isn’t just possible—it’s necessary.

Second Chance Day was coordinated by residents of RJD, supported by community volunteers and organizations focused on reducing recidivism. Booths offered information and referrals for legal services, education, mental health care, addiction recovery, and trauma-informed movement like PYP.

The reality is that 95% of incarcerated people will one day return to our communities. These services don’t just help while people are incarcerated—they benefit every person they’ll interact with once they’re released.

Hope is breaking bread while breaking down what it means to be human.

During lunch, I sat with four residents and my PYP Director. One man shared that he’d spent a decade in solitary confinement. Today, he’s studying for his master’s, writing a thesis on trauma, maintaining detailed murals on the prison yard, and building a nonprofit with his wife.

We discussed trauma—how it impacts our ability to “make good choices,” especially when the nervous system is stuck in survival mode.

Our lunch was deli croissant sandwiches, chips, cookies, and sodas (I must be a true West Coaster now—“soda,” not “pop”). I swapped chips with the man next to me, passed my cookie to another, and gave away my soda too.

Hope is knowing who this is for.

The man I shared snacks with asked me, “So, why prison? What makes you want to teach yoga here?”

It’s not a question I’m often asked by residents. I’ve always assumed my reasons didn’t matter—that my presence and the practice itself were enough.

But for me, it’s personal.

I think of a boy I grew up with, who’s spent most of his adult life in prison. We played tag, went to dances, ran track meets. He held my blocks, tried to teach me chess. He was a star football player with a beautiful singing voice.

But we didn’t grow up the same way. I had present parents, stable housing, no addiction or abuse in my immediate circle. He didn’t.

The last time I saw him in person was in a courtroom. So when I teach men who’ve made mistakes—one or many—I think of that little boy, and wonder who he might have become if he had what I had.

Hope is hearing people from within and outside the system say: we can do better—and we are.

One of the day’s highlights was a panel discussion that included formerly incarcerated people, restorative justice advocates, trauma educators, ministry leaders, and the former Secretary of CDCR.

They shared a vision of justice rooted in humanity and healing.

Hope is feeling the person next to you notice their breath.

The panel shared sobering statistics.

- Over 80 million Americans have a criminal record

- Nearly 44,000 legal barriers block access to housing, jobs, and education

- People with 4+ Adverse Childhood Experiences are 7x more likely to be incarcerated

- In California, it costs $133,000 annually to incarcerate one person

Beside me, a longtime yoga participant exhaled audibly. His shoulders dropped. I could tell he was using his breath to regulate his nervous system.

Hope is realizing that reform isn’t just moral—it’s economical.

Every $1 invested in prison education saves $4–$5 in reduced recidivism.

Rehabilitative programs improve quality of life for incarcerated individuals and correctional officers.

If just 25% of eligible people were released—with rehabilitative support—it would save California over $3 billion annually.

Since California adopted a rehabilitation-focused model, its recidivism rate is now 20–30% lower than the national average.

Hope is doing yoga in prison.

The panel ended with the question, “What gives you hope?”

That day at RJD was extraordinary—but not unusual. I see that same hope every Saturday in our classes on Echo Yard.

In quiet moments on the mat and conversations after class, I see people doing the hard work of healing. They are thoughtful, kind, present—with themselves and one another.

At the end of class, when 40 grown men lie quietly on their yoga mats—many of whom have committed serious crimes—I look around the gray prison gym and realize: I feel safer here than I do on the streets of downtown San Diego.

And it’s here, on Echo Yard at Donovan State Prison, that I continue to find hope.